Jan-Bart Gewald rewrites the colonial history of Zambia - an interview

In his new book Forged in the Great War: People, Transport, and Labour, the Establishment of Colonial Rule in Zambia, 1890-1920, Jan-Bart Gewald, Professor of Southern African History at Leiden University and senior researcher at the African Studies Centre, writes about the establishment of colonial rule in Northern Rhodesia, the current Zambia. When the British South Africa Company (BSAC) was awarded the territory by the British Crown in 1891, hardly any administration was established on the ground. In contrast to historians who argue that the colonial state nearly collapsed during the course of World War One (WWI, 1914-1918), Gewald argues that the establishment of effective colonial rule in Northern Rhodesia only came about on account of the unique conditions that developed in WWI. We interviewed Gewald at the ASC about his discoveries.

In his new book Forged in the Great War: People, Transport, and Labour, the Establishment of Colonial Rule in Zambia, 1890-1920, Jan-Bart Gewald, Professor of Southern African History at Leiden University and senior researcher at the African Studies Centre, writes about the establishment of colonial rule in Northern Rhodesia, the current Zambia. When the British South Africa Company (BSAC) was awarded the territory by the British Crown in 1891, hardly any administration was established on the ground. In contrast to historians who argue that the colonial state nearly collapsed during the course of World War One (WWI, 1914-1918), Gewald argues that the establishment of effective colonial rule in Northern Rhodesia only came about on account of the unique conditions that developed in WWI. We interviewed Gewald at the ASC about his discoveries.

Why did the British South Africa Company not establish effective colonial rule in Northern Rhodesia from the beginning?

‘The BSAC had no money! A territory three times larger than Great Britain was added to the Crown, but the BSAC spent all its money in the Chimurenga war in Southern Rhodesia (current Zimbabwe) and almost became bankrupt. The Colonial Office wasn’t giving them any money either; Northern Rhodesia was simply a bridge too far. So it existed on paper, but the BSAC was not capable of enforcing its will in the North.’

Can you give an example of this?

‘An administrator in Northern Rhodesia wrote: “The Bemba are restless. Please send a Maxim gun from Karonga”. But he can’t enforce it, he can’t do anything to make it come. So it doesn’t come.

Another example: The British colonial authority banned a specific form of agriculture (‘chitimene’) for which the local population chopped down trees, but the authorities didn’t have the means to enforce the ban. So the ban was lifted again.’

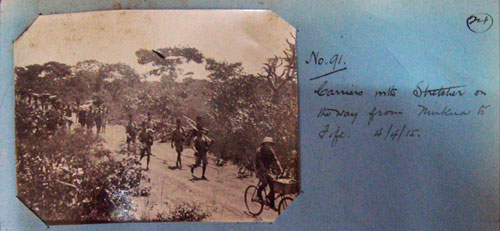

Carriers with stretcher on the way from Mukuha to Fife, 4/4/1915 (National Archives of Zambia).

How did World War I change this?

‘In WWI, the frontline in Africa was situated between German East Africa (current Tanzania) and Northern Rhodesia. Between the most northern track of the railway in Northern Rhodesia and the frontline, some 1,000 kilometers had to be covered. The British authorities couldn’t use animal transport because of sleeping sickness among animals, transmitted by the Tsetse fly. So they needed humans as carriers to transport goods: food and war material. Canoes were used for transport over waterways, some 14,000 canoes in total. Motorized transport was useless because it would require water, fuel and building roads to start with, which would have become too expensive.

In order to transport 1 ton of war material, 80,000 carriers were needed. The taxable adult male population in the area was 79,000. So this was a major operation of human labour.

Southern Congo already had mines and used thousands of men from Northern Rhodesia as labourers. These men were recruited as carriers in WWI. In addition, the British authorities paid chiefs and headman to obtain carriers.

The War Office in London made limitless funding available for this labour. This payment bound the chiefs and headmen to the colonial administration. So through the war, the colonial state was able to gain control over the people. Later on, from 1917, people were really forced to work as carriers, because there was a shortage of labour.’

Canoes (National Archives of Zambia).

In what respect does your historiography differ from the viewpoint of other historians?

‘Towards the end of the War, the Germans invaded Northern Rhodesia from the north. The British withdrew to the South. Other historians see in this withdrawal the collapse of the colonial administration. I don’t. I argue that, although it is true that there was a military retreat, this was not the same as a collapse in the administration. Indeed, I show that it was precisely on account of the war that the colonial administration could extend its influence and establish itself in the territory.’

In the end, what does your book show?

‘It shows that the legacy of World War I in Africa is far greater than we think. World War I was central to the establishment of colonial rule in Northern Rhodesia and thus to the history of Zambia. It shows that colonization was not a one-size-fits-all process in every country, and certainly not a similar process in Northern Rhodesia, Southern Rhodesia and South Africa for that matter.

To mention another example: World War I also meant a shift in people’s diet, from millet and sorghum to cassava and, later, maize. Millet and sorghum require extensive labour and can be more easily stolen; cassava is safe from thieves as it is grown in the ground.

World War I also linked people from Northern Rhodesia to people and ideas elsewhere. In 1919, a movement of Jehova witnesses, the ‘Watchtower’ movement, attacks the chiefs. They think the end of time has come, there is a Spanish Flu pandemic, the British have withdrawn from the north, and the Jehova witnesses say to people: “don’t listen to the chiefs that have made you work for the British”. But they are send off to jail by the British administration. These Jehova witnesses picked up their ideas from Southern Rhodesia. So you see an enormous movement of people, goods and ideas in that era.’

Fenneken Veldkamp