Rembrandt, Lion and Fox: the intimate relationship between art, media, philanthropy and wildlife conservation in Africa

We are deeply saddened to report that Dr Marcel Rutten passed away on 12 January 2020. This was the last blog post he wrote. Also read the In Memoriam.

Marcel Rutten was an ASCL senior researcher. His research activities concentrated on natural resource management, notably of land and water, in (semi-)arid Africa. In addition, his interest was directed to (eco)tourism and Kenyan politics.

This is the story of the intricate connection between the Old Dutch Masters, early nature research, an unhappy marriage, media, commercial interest and wildlife conservation in Africa; it’s a journey through time!

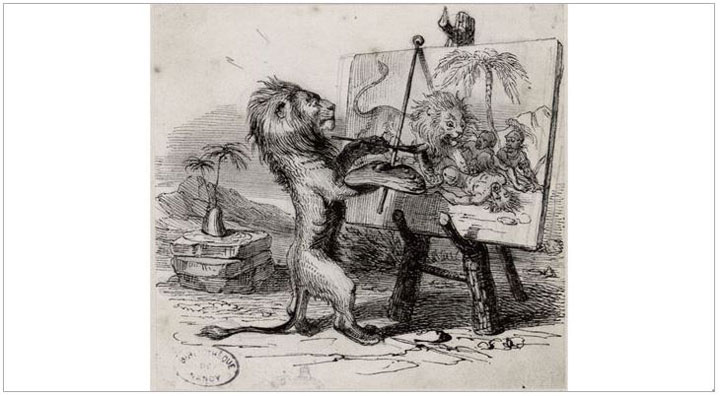

The Night Watch painting from 1642 by Rembrandt van Rijn (1606-1669) portrays a shooting company based in the city of Amsterdam. It is his most famous painting and millions of tourists have come to Amsterdam to admire this extraordinary piece of art. Less well known are Rembrandt’s drawings of exotic animals like lions and elephants. For long, these animals could not be seen in Amsterdam as the Romans had been able to in their Colosseum, many centuries earlier. It is only in the Golden Age that the Dutch East India Company (VOC), the world’s first multinational company created in 1602 to trade in coffee and spices, transported an elephant and a lion to the Dutch Republic. The animals were placed in a ‘menagerie’, where they could be viewed by the public. Rembrandt was one of the spectators and, as a result of these live observations, he was able to portray an elephant and lions.

Young Lion Resting, Rembrandt van Rijn, ca. 1638–42. Black chalk, white chalk heightening, and gray wash, on brown laid paper. Dimensions 11.5 x 15 cm. The Leiden Collection

Wealthy VOC merchants

But the Dutch master is best known for his stunning portraits commissioned by the well-to-do of Amsterdam society, VOC merchants as well as artists. One of them, who would become a good friend of Rembrandt, was the wealthy poet and art collector Jan Six (1618-1700). Another was the famous Dutch poet Pieter Corneliszoon van Hooft (1581-1647), who gave his name to the most prestigious Dutch prize in literature: the P.C. Hooft Prize. The son of a wealthy VOC merchant, he studied law and was appointed bailiff of Gooiland, a rural area some 20 km to the south-east of Amsterdam. Van Hooft and his wife resided both in Amsterdam and in Muiderslot Castle. In 1634, he bought a large plot for investment purposes in nearby ’s-Graveland. The city of Amsterdam needed sand for its territorial expansion, which was purchased from this rural area. In short, fortunes garnered by the Dutch from the trade in spices and slaves in the East and West were re-invested at home in exclusive housing, land and art.

Gooilust

The Golden Age fortunes passed on to the new generations. The land once owned by P.C. Hooft, however, was now in the hands of Gerrit Corver Hooft, no relative, who, as head of the West Indies Company, also made his money from trading with exotic places. In 1779, Corver Hooft decided to build a country house. In 1895, the estate ended up in the hands of Lady Louise Digna Six, a distant relative of both Gerrit Corver Hooft and Jan Six, Rembrandt’s friend. Lady Louise Digna Six became the new owner of Gooilust, as the country house had been named.

Private zoo

Private zoo

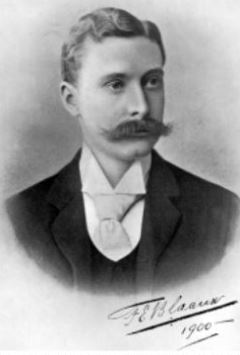

By now, dear reader, you must be wondering if the content of this blog matches the title? To show it does, I must introduce you to one other character: Frans Ernst Blaauw, husband to Lady Louise Digna Six. Born in Amsterdam in 1860, he had always shown a keen interest in plants and animals, notably birds. He made several journeys to South and North America and South Africa. His findings were published in nature magazines. For forty years, until his death in 1936, Blaauw lived at Gooilust and turned the 97-hectare estate into a private zoo. He specialized in safeguarding species threatened with extinction and through his growing collection developed a huge knowledge about exotic plants and animals. He kept kangaroos, white tail gnus, antelopes, bison, wisent, ostriches and several rare birds. Blaauw initiated breeding programmes for these species and directors of zoos and animal parks from all over Europe visited him to buy these animals.

To British East Africa by steamboat

On 24 March 1924, Blaauw embarked on a trip to British East Africa by steamboat. On 18 April, the ship arrived in the harbour of Mombasa. A few days later, he took the Uganda Express train to Nairobi, where he settled at the Norfolk Hotel. Carrying a letter of introduction from the Zoological Society of London, he contacted Game Warden Captain Ritchy, seeking support for a safari to the Southern Game Reserve, home of many wild animals as well as the Maasai pastoralists. His guide was the professional hunter Bill Judd, who had accompanied former US President Theodore Roosevelt during a safari trip in 1909-10. Judd was smashed to death by an elephant a few years later in 1927. Blaauw’s safari had a very different aim than most of the sports hunting safaris of that time. Blaauw’s objective was solely to watch animals and plants. In the introduction of his book Searching for Animals and Plants in British East Africa, published in 1927, Blaauw expresses his gratitude to Judd for taking care of him and for being so willing to set aside being a ‘professional hunter’ and to respect and adapt to Blaauw’s objective to observe flora and fauna as a nature researcher.

Not amused

Louise Six, however, was not amused by her husband’s fanatical hobby of keeping exotic animals. She would later disinherit her husband and leave the mansion to the first nature organization in the Netherlands: Vereniging tot Behoud van Natuurmonumenten (Society for Preservation of Nature Monuments in the Netherlands). The Society was founded in 1905 to fight a waste dumping belt proposed for the city of Amsterdam and still resides at Gooilust today. But, as a result of Louise’s will, we can no longer admire the exotic plants and animals at Gooilust. The plants withered and the animals, or what was left of them, were donated to the Duke of Bedford, a friend of Blaauw, and President of the Zoological Society of London from 1899 to 1936. Still, the one-time presence of the Blaauw zoo in the area, now part of the city of Hilversum, is remembered in a nearby high-end residential area, built in 1909. Blaauw suggested that the names of the streets in this new block be inspired by the animals he cared for: Gnu Lane, Crane Lane, Ostrich Lane, etc, which indeed happened.

Shooting lions

From 1900, hunting in the Southern Game Reserve was not allowed except by game control officers. A few years before Blaauw’s Kenya visit, the aptly named game control officer John Alexander Hunter was ordered by Captain Ritchy to shoot over 100 lions in the Kajiado area during a period of a few months. Due to a major drought, thousands of cattle had died and lions scavenging the Maasai plains littered by carcasses had increased in huge numbers.

Conservation programmes in Kajiado County

Conservation programmes in Kajiado County

We jump one century forward and revisit the same Maasai area that Blaauw observed. With the exception of 1952-1997, sports hunting is still prohibited. However, as in the past, the Maasai occasionally kill a lion in self-defence, following an attack on humans or livestock. Groups of Moran, the warrior group of the Maasai which comprises the younger unmarried males, might also kill a lion to show their bravery. Foreigners, now mostly Americans, run conservation programmes in south-eastern Kajiado County, most notably financing predation compensation programmes in an attempt to safeguard and expand the number of lions present:

(1) The Predator Compensation Fund (PCF), put in place in 2003, of the Maasailand Preservation Trust (MPT);

(2) Lion Guards, started in 2007, is an offshoot of Living With Lions, primarily a group of wildlife biologists conducting research in Kenya, financed by Panthera, Arthur Blank Family Foundation (a charity of the co-founder of The Home Depot, the world’s largest home improvement retailer), and Philadelphia Zoo, among others;

(3) National Geographic Maasai Emergency Fund (2008) run by National Geographic Society Explorers-in-Residence, filmmakers and safari company owners Dereck and Beverly Joubert.

Philanthropists

The first predator compensation scheme, PCF, ran into financial problems by 2010 but was rescued by National Geographic wildlife photographer Nick Brandt, who, together with American businessman Tom Hill and Kenyan tour operator Richard Bonham, who initiated the PCF, started a new organization called Big Life Foundation. Initially, using some of Brandt’s own funds and through buyers of his art photography, Big Life became a major player in the region, employing and equipping several hundred game rangers and controlling some 1.6 million acres across the Kenyan-Tanzanian border. The key funders of the initial US$700,000 seed money for Big Life are billionaires Stan and Fiona Druckenmiller and Stan and Kristine Baty. As philanthropists who made fortunes in the financial sector, i.e. hedge funds and real estate, they had been donating to many other charities, including other wildlife groups such as Tusk. At one time, Big Life and the National Geographic Maasai Emergency Fund, the latter becoming the National Geographic Big Cats Initiative in 2009, merged their activities in the Amboseli region. Big donors in the Big Cats Initiative are Oracle and the Lion Recovery Fund, which was set up by The Leonardo DiCaprio Foundation and the Wildlife Conservation Network. Other groups supported by the Lion Recovery Fund include African Parks, which runs several game parks in Africa and was started by the late Dutch billionaire Paul Fentener van Vlissingen - who made his fortune in energy (esp. coal) and animal feed through SHV Holdings, the Netherlands largest family-run company -, Big Life, Kenya Wildlife Trust, Panthera and many other groups actively supporting the lion.

‘Fox’ helped to save the lion

Since the 2010s, this consortium of wildlife photographers, filmmakers, movie actors, safari companies and lodge owners, media houses and wildlife conservation groups has poured millions of US dollars into the Maasai area. The National Geographic Society (NGS) stands out among this network of groups and organizations. NGS has been reaching out to the wider public popularizing wildlife conservation through their magazine and television network. The (US) National Geographic Channel was started in 2001 and ownership was 27% by NGS and 73% by Rupert Murdoch’s 21st Century Fox. So, Fox helped to save the lion, but in March 2019, it was ‘grabbed’ by the ‘Lion King’, when Walt Disney took over Fox’s 73% share in the National Geographic Channel. Besides the ethical motives these partners will have for interfering in Africa’s conservation and development efforts, one cannot ignore the thought that commercial interests are a key driving force.

Where are the local Kenyan authorities?

The profound marketing knowledge of media houses and wildlife NGOs alike, used to transmit the ‘alarming’ message about threats to wildlife and to raise funds is exemplified in the humanization of lions, elephants and rhinos: the animals are given names and a CV and can be ‘adopted’ for money. For sure, wildlife groups would have a hard time paying for conservation activities out of their own pockets or through revenues made from wildlife-tourism related businesses without external (primarily US) funds. In fact, the key donors and, consequently, the key wildlife managers in southern Kenya are Americans, who provide part of their wealth, which was generally made in real estate, retail, trade or through hedge funds. Moreover, public funds from UN agencies such as UNDP and UNEP, the World Bank, the European Union and especially the USA (USAID, US Embassy, US Department of the Interior) are crucial to financing a large number of Kenyan wildlife organizations that, through their activities and input, impact on Kenyan wildlife law making and wildlife policy. It triggers the question: what is the position and role of the Kenyan authorities and the local Maasai in managing their own local resources within the broader perspective of sustainable economic development, especially safeguarding and improving the local livestock sector?

Collectors of Old Dutch Masters

One final observation can be made to conclude this journey in time and to bring us back to Rembrandt van Rijn. Rembrandt and wildlife conservation were not only combined through Louise Six and Frans Blaauw. In fact, there is a modern version of the Blaauws: billionaires Daphne and Thomas Kaplan, the founders of Panthera, an organization geared at conserving wild cats worldwide which they established in 2006. Besides Panthera’s activities in Kajiado County mentioned above, they have been sponsoring a wild cat programme at Oxford University and funding many other charities. But the Kaplans are also known for their fascination with the paintings of Rembrandt van Rijn. Since 2003, their collection has been growing and they are the proud owners of the largest private collection of paintings and drawings by Rembrandt and other Dutch 17th century painters in the world: The Leiden Collection. And yes, Rembrandt’s drawing of a young lion is part of these over 250 objects.

As a post-script, we should mention another couple: John Kay and Jutta Maue and their foundation. They are former band members of Steppenwolf, best known for their hit song ‘Born to be Wild’. Their KayMaue foundation donates money to saving Amboseli’s elephants. But that is a story for another moment in time.

Photo left: Young Lion Resting, Rembrandt van Rijn, ca. 1638–42. Black chalk, white chalk heightening, and gray wash, on brown laid paper. Dimensions 11.5 x 15 cm. The Leiden Collection (accessed December 6, 2019)

Photo right: Loss of Maasai cattle due to lion attacks. Photograph in the collection of Marcel Rutten, photographer unknown.

This post has been written for the ASCL Africanist Blog. Would you like to stay updated on new blog posts? Subscribe here! Would you like to comment? Please do! The ASCL reserves the right to edit, shorten or reject submitted comments.

Read the former ASCL Africanist Blog post Salafists and the Missing State in the Sahel, written by Rahmane Idrissa.

Add new comment