In Memoriam: Ousmane Dan Galadima (1927-2018)

Klaas van Walraven is a historian and political scientist working on the history of colonialism and decolonisation in French Equatorial Africa.

On 5 October, Ousmane Dan Galadima, a leader of the Sawaba movement and commander of its guerrilla army, died in Madaoua, Niger. Dan Galadima was one of the most important leaders of Sawaba, the nationalist movement that formed Niger’s first autonomous government during the struggle for independence.

Born into a chiefly family, he remained outside the circles of traditional power and worked as an interpreter for the colonial administration. A convinced Marxist, he was a confidante of Sawaba’s charismatic leader, Djibo Bakary, and began his party career as organisational secretary. Later, he became assistant secretary-general. He was one of the movement’s fiercest agitators, fighting the French as well as social strata in Niger standing in the way of the emancipation of semi-urban ‘petit peuple’, who formed the backbone of the nationalist movement. Elected to the National Assembly for the city of Madaoua (1957), Dan Galadima was an energetic member of parliament, an active debater of socioeconomic issues and a critic of Niger’s emergent elite. He also had a sharp tongue – French administrators hated him, likening him to Ho Chi Minh (whom some say he resembled).

Clandestine life

Dan Galadima spent the period of the infamous referendum on France’s Fifth Republic in jail (September 1958) – like other hardline Sawabists, he had pleaded for the assumption of immediate independence. Consequently, the French staged a constitutional coup d’état and began to persecute the movement, assisted by their clients of the Rassemblement Démocratique Africain (RDA), a party they helped bring to power in order to safeguard France’s influence.

It marked the beginning of Dan Galadima’s clandestine life, which was also part of the broader history of Third World revolutionary struggles unfolding during the 1950s-1960s. Forced to flee the country, Ousmane Dan Galadima worked tirelessly to establish a network of Sawaba cells in neighbouring countries with which to stage infiltration operations and prepare for a guerrilla struggle to recapture power. In 1961, he organised the Sawaba network in Kano, Northern Nigeria, after which he established himself in Morocco to channel Sawaba recruits for guerrilla training in Algeria. He was already in touch with Frantz Fanon – the famous Martiniquan writer, Third World philosopher and FLN revolutionary – when the Algerian nationalists were fighting for independence and opened their southern front. Later, Dan Galadima established himself in Algeria itself. There, he (besides other Sawabists) met members of other African liberation movements, including Nelson Mandela, Amilcar Cabral and Samora Machel as well as the global revolutionary icon of the age – Che Guevara. Galadima would meet Che again in Nkrumah’s Ghana, where he settled to assemble the guerrilla forces and prepare the onslaught on the RDA regime. Dan Galadima travelled widely, speaking at the All-African Peoples’ Conference in Tunis, making an undercover trip to Marseilles, visiting North Vietnam and, on two occasions, communist China.

It marked the beginning of Dan Galadima’s clandestine life, which was also part of the broader history of Third World revolutionary struggles unfolding during the 1950s-1960s. Forced to flee the country, Ousmane Dan Galadima worked tirelessly to establish a network of Sawaba cells in neighbouring countries with which to stage infiltration operations and prepare for a guerrilla struggle to recapture power. In 1961, he organised the Sawaba network in Kano, Northern Nigeria, after which he established himself in Morocco to channel Sawaba recruits for guerrilla training in Algeria. He was already in touch with Frantz Fanon – the famous Martiniquan writer, Third World philosopher and FLN revolutionary – when the Algerian nationalists were fighting for independence and opened their southern front. Later, Dan Galadima established himself in Algeria itself. There, he (besides other Sawabists) met members of other African liberation movements, including Nelson Mandela, Amilcar Cabral and Samora Machel as well as the global revolutionary icon of the age – Che Guevara. Galadima would meet Che again in Nkrumah’s Ghana, where he settled to assemble the guerrilla forces and prepare the onslaught on the RDA regime. Dan Galadima travelled widely, speaking at the All-African Peoples’ Conference in Tunis, making an undercover trip to Marseilles, visiting North Vietnam and, on two occasions, communist China.

‘Scorpion’

In many ways, Dan Galadima was a person larger than life. In contrast to other members of Sawaba’s leadership, he was popular with the rank and file. As chief of staff, he visited the guerrillas in their hideouts, bringing money, giving advice and informing himself about local circumstances. He was seen as someone not afraid of uncomfortable conditions and who cared little for luxuries (as evidenced in the later stages of his life). His courage, in combination with his unassuming posture, earned him the nickname ‘scorpion’. By 1964, Galadima moved to Porto-Novo, Dahomey (now the Republic of Benin), to establish a forward command post for the military operations against Niger’s regime. The failure of Sawaba’s onslaught left Galadima – and other Sawabists – in the political wilderness. But this unswerving revolutionary did not lose faith; instead he searched for new ways to rid Niger of its neocolonial regime (he tried to interest the army in helping to overthrow the RDA). It all came to naught, and personal disaster struck in 1967 when he was arrested in Nigeria and extradited to Niger. Brought to the French-run security services in the presidential palace, Galadima was very badly tortured; he had to be resuscitated in hospital before being subjected to new rounds of interrogation. His tormenters tried to persuade him to make his peace with the RDA, but the little Marxist refused, rejecting the legitimacy of the French-installed regime.

Incarcerated

He was incarcerated with other Sawabists in Tahoua. In 1969, he was sentenced to death. Two years later, this was commuted to life imprisonment. The army coup of Seyni Kountché in 1974 brought relief, albeit temporarily. Sawabists were freed and so was Galadima. He would have been offered an ambassadorship to the GDR but refused, fearing the new regime wanted him out of the way. Soon, he and leading cadres fell victim to Kountché’s paranoia and were rearrested. They were taken to a camp in Dao Timmi, in the Totomaï mountains, deep in the Sahara (1976). With escape out of the question, Dan Galadima spent four or five years in isolation.

Whatever one thinks of his ideological convictions, they were the source of personal strength. Thus, a decade later he participated in the National Conference (1991), which ended the closure brought about by France’s intervention in Niger’s politics, three decades earlier. Every day Galadima walked to the conference venue, participating in the deliberations and delivering a speech on the repression of Sawaba’s cadres.

Fighting spirit

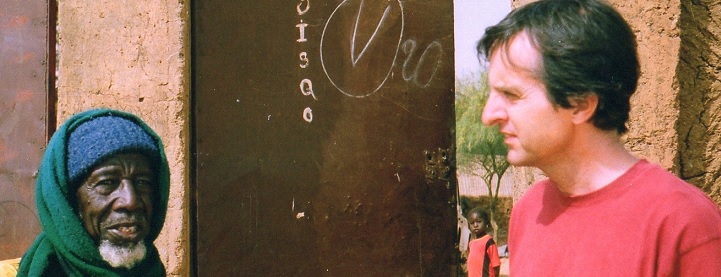

Another ten years later – when I met him for the first time – he had lost nothing of his fighting spirit. We spoke several times during the following decade (2003, 2006, 2008 and 2013). Having survived the worst a human being can go through, he seemed without fear. The ‘scorpion’ continued to criticise government policy (to the point of telling President Tandja to his face what he did wrong). Popular admiration for his courage and simple life made him untouchable. In 2006, before another interview, he had just been to see Madaoua’s prefect to discuss the famine of the previous year, a file still in his hand. Two years later, at the age of 81, Dan Galadima had moved to family in Niamey for medical care. Sitting on a mattress in an austere dwelling and surrounded by his papers, a transistor radio within reach, Sawaba’s revolutionary was as informed about current affairs as ever, arguing against globalisation, criticising France, and fulminating against Niger’s kleptocratic politicians (who were having two meals a day!). This small, frail man could still have captivated a crowd.

Getting to know such an extraordinary personage has been one of the privileges of writing my history of the Sawaba movement. I met Dan Galadima for the last time in November 2017. Visiting him in a run-down compound in a Niamey slum, I brought him the French version of my book. Emaciated and lying on a mat in circumstances that can only be described as abject poverty, he recognised me, accepted the book and mumbled something about the French – his struggle was not over yet. Mine was: I felt as if I had repaid a debt. Whatever one’s opinion on the stances and actions of different movements in the struggles of the post-independence era, the death of Ousmane Dan Galadima (91) marks a moment in time. Niger has lost a remarkable son.

Literature:

- The Yearning for Relief: A History of the Sawaba Movement in Niger (Brill: Leiden & Boston, 2013)

- Le Désir de calme : L’histoire du mouvement Sawaba au Niger (Presses Universitaires de Rennes: Rennes, 2017)

Photos:

Top photo: Ousmane Dan Galadima with the author, Madaoua, 2006. Photo collection Klaas van Walraven.

Upper photo: Ousmane Dan Galadima in the 1950s. Photo from publication Parti Sawaba. Pour l’Indépendance effective du Niger: Les raisons de notre lutte (Bureau du Parti SAWABA: Bamako, 15 Jan. 1961)

Lower photo: Ousmane Dan Galadima, Niamey 2008. Photo: Klaas van Walraven.

This post has been written for the ASCL Africanist Blog. Would you like to stay updated on new blog posts? Subscribe here! Would you like to comment? Please do! The ASCL reserves the right to edit, shorten or reject submitted comments.

Comments

Add new comment

Un digne fils d'Afrique vient de nous quitter.

Le sentiment que j'ai c'est comme si lui et ses compagnons de lutte ont sacrifié leur vie pour rien. Au final ils n'ont reçu aucune reconnaissance ni même le Sawaba, la délivrence, pour laquelle ils ont lutté.

Au vu de l'évolution de l'Afrique francophone depuis 1960 on constate clairement que leur option contre ce qui est devenu courament appelé la "françafrique" était juste. Ils ont été les premiers en "Afrique occidentale française" à dénoncer la construction de ce néocolonialisme français et ils l'ont payé très cher. Pierre Mesmer l'a dit lui même concernant des mouvements comme le Sawaba et l'UPC, "on a accordé l'indépendance à ceux qui la réclamait le moins après avoir éliminé ceux qui l'ont réclammée avec le plus d'intransigeance".

Au Niger on a eu donc des militants africains de la trempe des Lumumba, des Moumié, des Cabral mais on les a recouvert du voile de l'anonymat le plus total.

J'éprouve un grand sentiment de tristesse avec cette perte, c'est comme si mon dernier héros venait de partir. Il aura cotoyé des grandes lumières du panthéon africain comme Ben Barka, Frantz Fanon, Modibo Keita, Kwame Nkrumah, Samorah Machel etc... Que son âme repose en paix.

Je remercie l'auteur du livre et de cet hommage Mr Van Walraven, qui contribue énormément par ses travaux à lever petit à petit ce voile d'ombre sur cette partie de notre histoire.