Bridging across islands and generations: Swahili heritage in digital futures

On 28 January, inside the coral-stone walls of the Lamu Fort Library (Lamu island, northern Kenyan coast) and hosted by Head Librarian Khadija Issa Twahir, Annachiara Raia convened a first pilot roundtable dedicated to the question on how to collaborate in safeguarding and connecting enduring heritage along the Swahili coast.

What does it mean to preserve heritage on the small islands of the East African Indian Ocean? On the Lamu Archipelago, preservation is not only about safeguarding fragile manuscripts or digitising aging cassettes. It is about relationships - between islands, generations, and memory and technology. The conversations in Lamu unfold against a broader misconception that still shapes global cultural hierarchies: the persistent idea of a ‘southern cultural weakness’, which frames regions in Africa or Latin America as spaces of restricted literacy or limited literary production due to their geopolitical location. The realities of the Swahili coast tell a different story.

Sophisticated cultural history makers

On these remote islands, barefoot bards and female poets engage rigorously with inherited traditions and contemporary concerns through texts and performance. Their work is neither marginal nor lacking in literary capital. These local intellectuals are sophisticated cultural history makers whose scripts and practices circulate dynamically along the coast - even if they remain insufficiently heard in the Global North. Digitisation, in this context, is not neutral. It is part of a larger effort to rebalance visibility and support traditions that already possess depth, authority, and historical continuity. The question is not how to ‘give voice’ to Lamu’s custodians, but how to collaborate in safeguarding and connecting what already exists. On Wednesday 28 January, inside the coral-stone walls of the Lamu Fort Library and hosted by Head Librarian Khadija Issa Twahir, Annachiara Raia convened a first pilot roundtable dedicated to this question.

Listening, exchanging, and exploring

Listening, exchanging, and exploring

Organised with Fahim Abdalla, Nayma Idris, Mahmoud Ahmed Abdulkadir and Thomas Gesthuizen, the roundtable brought together ten local heritage custodians known over the years as invaluable keepers of Swahili literary and musical traditions. The aim was simple but ambitious: to listen, exchange ideas, and explore whether - and how - personal and community collections might be shared digitally and through open-access platforms for future generations. This initiative builds on earlier work to preserve part of Ustadh Mau’s private poetry and Friday sermon collection (supported by UCLA Library’s Modern Endangered Archives Program). Encouraged by that experience, we are preparing a new grant proposal to expand these efforts, seeking to identify, protect, and connect endangered collections across the Swahili coast - always under the guidance and participation of their custodians.

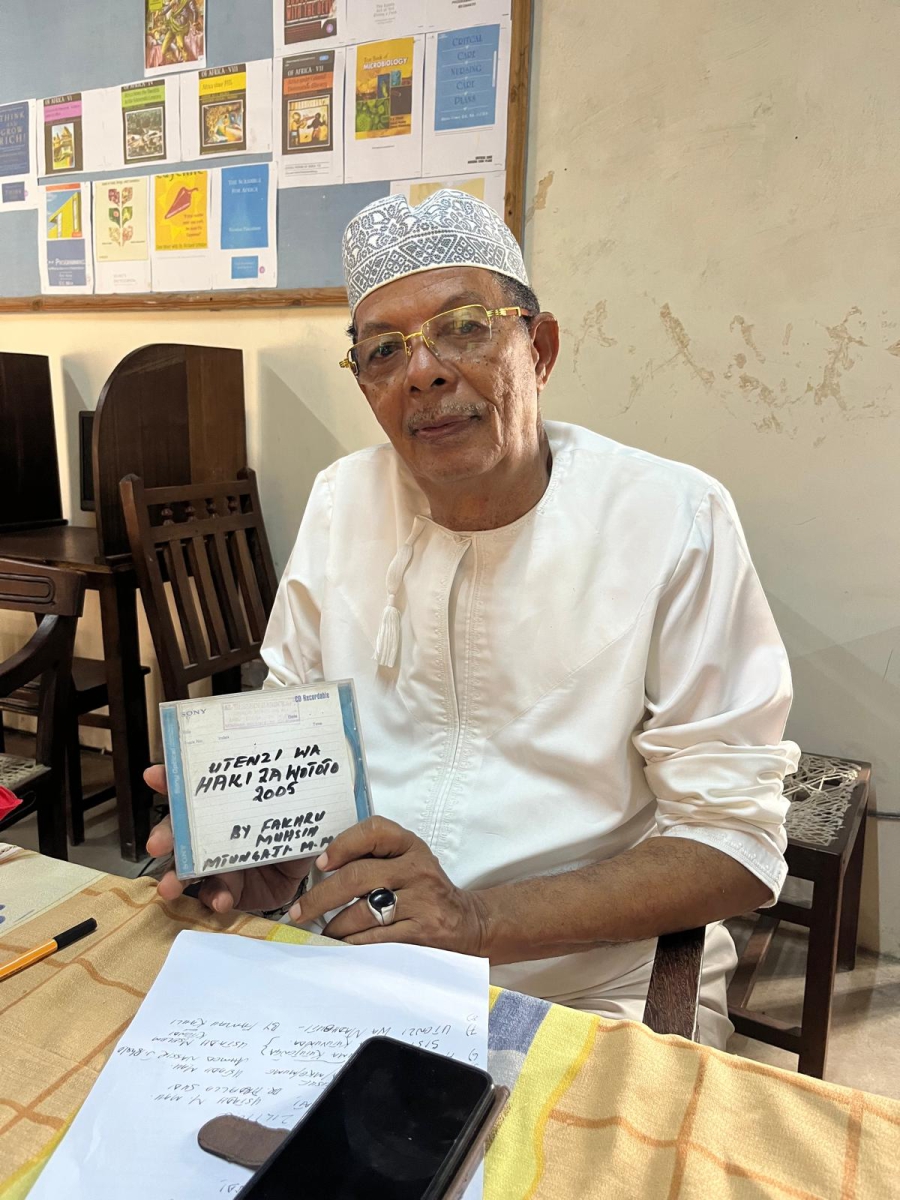

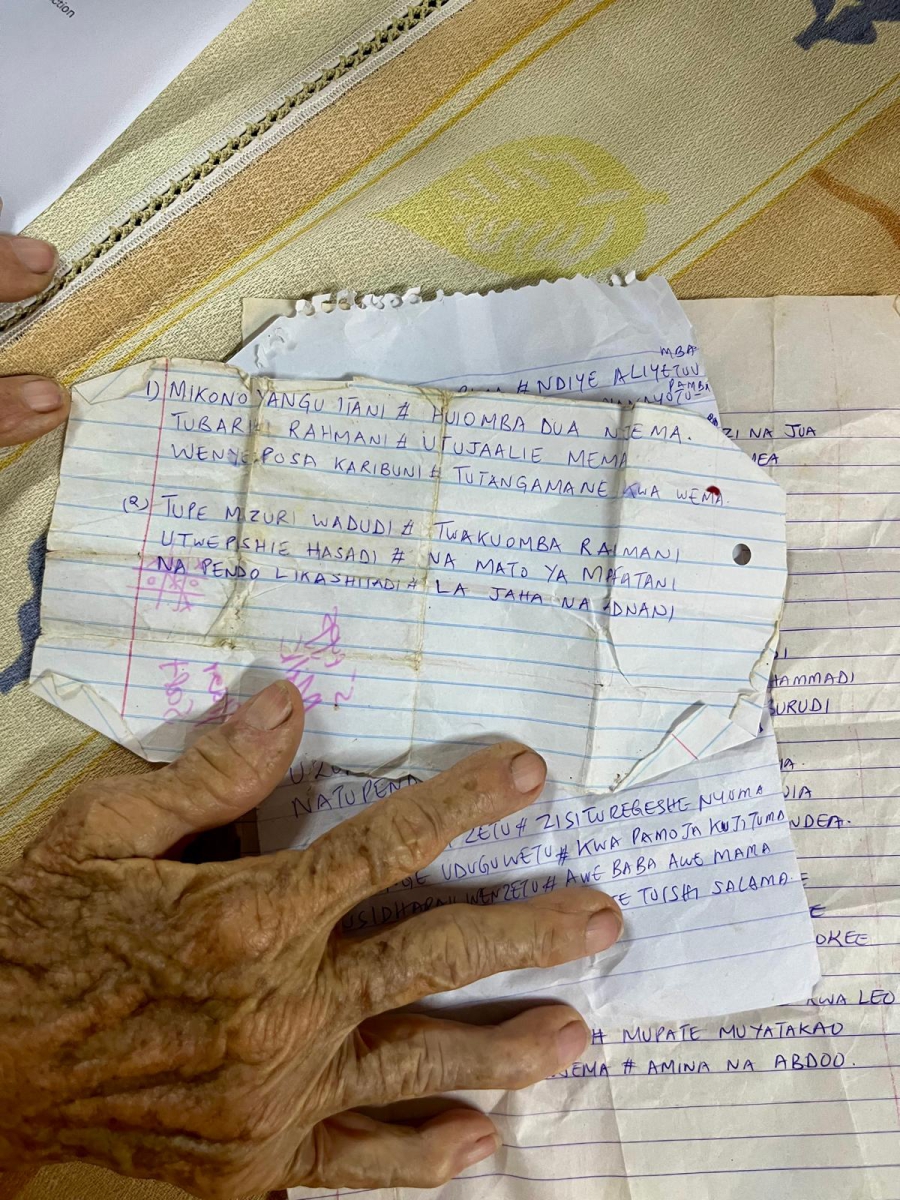

Heritage on these islands exists in many forms. Some participants of the roundtable arrived carrying tangible traces of their grassroots archives: loose sheets, floppy disks, aging CDs, and black-and-white photos. Others arrived empty-handed - because everything they preserve lives in memory. Their archive is embodied in voice, recitation, and performance. Among the custodians were two distinguished female intellectuals from Faza and Pate. Bi Zwena of Faza is renowned for reading aloud oral poetry and historical narratives in Kibajuni. From Pate, Bi Ridhai shared reflections rooted in her island’s intellectual traditions. Their presence highlighted the central and often under-recognised role of women in sustaining Swahili literary and oral heritage.

Christina Aarts, known in Lamu as Mama Subira, also joined. Originally from Sweden, she has lived on the island since 1974 and recorded music festivals whose tapes now risk deterioration. As she noted, Siu Island, once a celebrated centre of scriptoria along the Swahili coast, was home to musical associations such as the Jamhuri and Eleven clubs. Lamu Island had the Harambe Music Club. These institutions formed social and artistic networks deserving renewed attention and preservation.

Male custodians brought energy and commitment. Khalid Omar, a celebrated taarab singer and regular winner of local poetry competitions, reflected on performance as both art and archive. Muhammad Lali, known for violin performances interwoven with Swahili verse, emphasised the inseparability of music and poetry. Cassette and CD kiosk owners, including Bwana Ghalib Mughadar and Amani Studio, contributed practical insights into circulation, reproduction, and the complexities of intellectual property in the digital age.

Male custodians brought energy and commitment. Khalid Omar, a celebrated taarab singer and regular winner of local poetry competitions, reflected on performance as both art and archive. Muhammad Lali, known for violin performances interwoven with Swahili verse, emphasised the inseparability of music and poetry. Cassette and CD kiosk owners, including Bwana Ghalib Mughadar and Amani Studio, contributed practical insights into circulation, reproduction, and the complexities of intellectual property in the digital age.

Sustaining living networks of knowledge

The roundtable achieved its purpose: it tested the waters. In an open and respectful atmosphere, we began reflecting on how to honor, reenact, and gently preserve local histories without removing them from their social contexts, while also embracing digital technologies and open-access infrastructures. Preserving Swahili heritage on small islands is not simply about archiving the past. It is about sustaining networks of knowledge that remain vibrantly alive. It requires care, trust, and recognition that archives are dispersed across households, islands, memories, and media.

What emerged from this first gathering was not only the outline of a future project, but a shared commitment: to ensure that the written and oral worlds of the Swahili coast continue to circulate across seas, across generations, and, increasingly, across digital spaces.

What emerged from this first gathering was not only the outline of a future project, but a shared commitment: to ensure that the written and oral worlds of the Swahili coast continue to circulate across seas, across generations, and, increasingly, across digital spaces.

Keywords: African literature; constructing heritage; languages and cultures of the world; languages, cultures and worldviews; Swahili literature and intellectual history; Digital media;