Book acquisition trip to Rwanda during the COVID-19 pandemic

At last, the university granted us permission to travel again! My colleague Gerard van de Bruinhorst and I had planned an acquisition trip to Rwanda in the last week of September. We had not been there before and were particularly curious to know how the country’s language policy had shaped the publication landscape of this formerly francophone country. In 2003, English had become an official language and in 2010 it had become the official language of instruction. Moreover, Rwanda was the only African country coloured yellow on the ‘COVID-19 map’ on the website of the Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs, which meant the health risks were deemed acceptable. Just three percent of Rwanda’s population has been vaccinated, so to be cautious, I had ordered FFP2 face masks and brought a whole lot of bottles with disinfectant to put in my otherwise empty suitcase, along with another empty bag, all to be filled with books on our return.

At last, the university granted us permission to travel again! My colleague Gerard van de Bruinhorst and I had planned an acquisition trip to Rwanda in the last week of September. We had not been there before and were particularly curious to know how the country’s language policy had shaped the publication landscape of this formerly francophone country. In 2003, English had become an official language and in 2010 it had become the official language of instruction. Moreover, Rwanda was the only African country coloured yellow on the ‘COVID-19 map’ on the website of the Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs, which meant the health risks were deemed acceptable. Just three percent of Rwanda’s population has been vaccinated, so to be cautious, I had ordered FFP2 face masks and brought a whole lot of bottles with disinfectant to put in my otherwise empty suitcase, along with another empty bag, all to be filled with books on our return.Even before entering the country, we discovered that Rwanda is well-organised: anyone wanting to visit must present a negative COVID-19 test result. Upon arrival at Kigali airport, a second test is required. What’s more, you cannot leave the country before doing a third test.

We arrived on Friday evening, and the Saturday appeared to be ‘Umuganda Day’: every last Saturday of the month people come together to do community work between 8:00 and 11:00. This is compulsory and many shops - including bookshops - only open after 11:00. Luckily, we received our negative test results fairly early, so we could go outside and see people doing all kinds of chores, from weeding and sweeping the streets to carpentry and bricklaying. Rwanda is sometimes called the Singapore of Africa and indeed, Kigali looks like a booming city with beautiful, well-tended parks and lots of greenery (walking on the lawns is forbidden). The streets are very clean. Unlike many other places in Africa, there are no plastic bags hanging in trees. In Rwanda, it is forbidden to import or use plastic bags, with high penalties if you get caught. There are no informal stands along the road where food is prepared to sell to passers-by (it’s forbidden). According to our taxi driver, who came from a border region close to Uganda, this explains the difference in build between Rwandans (rather frêle) and Ugandans (rather robust): the latter can eat at the side of the road!

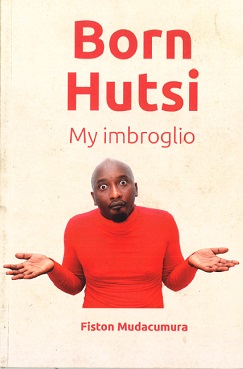

Walking the streets in Kigali, there are constant reminders of 1994, the year the genocide took place. On our way to the first bookshop, we passed the first of many memorials we would encounter, also near churches, where, during the genocide, people were not always safe either. Most Rwandans are Christian, but after 1994, many people became Muslim, out of frustration with the Church’s attitude during the genocide. One of the main memorial sites, the Kigali Genocide Memorial Center, has an impressive museum (the ‘Room of the children’ is heart-breaking), a bookshop, and gardens where the remains of victims still found all over Rwanda are re-buried and their names engraved on marble walls. Travel guides warn visitors to Rwanda not to distinguish between Hutu or Tutsi (as was done in colonial times); you cannot ask somebody which group she or he belongs to. When an American tourist asked during a guided tour how many Tutsi were now living in the country, the abrupt response was that this was not being recorded. Her husband urgently whispered something to her, upon which she declared loudly ‘I was only asking’. The official motto is to reconcile and to forgive, but not to forget.

Walking the streets in Kigali, there are constant reminders of 1994, the year the genocide took place. On our way to the first bookshop, we passed the first of many memorials we would encounter, also near churches, where, during the genocide, people were not always safe either. Most Rwandans are Christian, but after 1994, many people became Muslim, out of frustration with the Church’s attitude during the genocide. One of the main memorial sites, the Kigali Genocide Memorial Center, has an impressive museum (the ‘Room of the children’ is heart-breaking), a bookshop, and gardens where the remains of victims still found all over Rwanda are re-buried and their names engraved on marble walls. Travel guides warn visitors to Rwanda not to distinguish between Hutu or Tutsi (as was done in colonial times); you cannot ask somebody which group she or he belongs to. When an American tourist asked during a guided tour how many Tutsi were now living in the country, the abrupt response was that this was not being recorded. Her husband urgently whispered something to her, upon which she declared loudly ‘I was only asking’. The official motto is to reconcile and to forgive, but not to forget.

On entering one of the main bookshops, Caritas, the many book covers with titles referring to one aspect or another of the genocide stand out. Academic studies, local histories, autobiographies, collections of interviews, personal narratives, and documentaries deal in different ways with this catastrophic event. The language of the books is interesting. Although English replaced French as official language of instruction in public education in 2010, many books are still published in French, alongside Kinyarwanda (spoken by 99 percent of the population). Consequently, books seem to be regularly published in three languages: English, French, and Kinyarwanda. When speaking with people, it transpires that sometimes they still feel more comfortable discussing in French.

On entering one of the main bookshops, Caritas, the many book covers with titles referring to one aspect or another of the genocide stand out. Academic studies, local histories, autobiographies, collections of interviews, personal narratives, and documentaries deal in different ways with this catastrophic event. The language of the books is interesting. Although English replaced French as official language of instruction in public education in 2010, many books are still published in French, alongside Kinyarwanda (spoken by 99 percent of the population). Consequently, books seem to be regularly published in three languages: English, French, and Kinyarwanda. When speaking with people, it transpires that sometimes they still feel more comfortable discussing in French.

We were surprised to find that Ikirezi, one of the other big bookshops, has a Dutch owner. It has a café and Wi-Fi, so we could instantly check titles in the Leiden university catalogue.

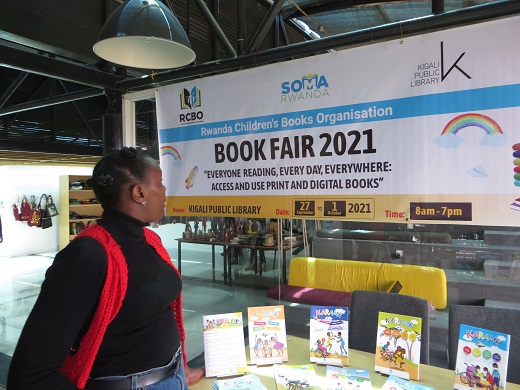

Another surprise was the bookfair we discovered, probably one of only a few being organised in Africa this year due to the COVID-19 restrictions. The Children’s Bookfair organised by The Rwandan Children’s Book Organisation (RCBO), was held on the top floor of the Public Library in Kigali, and we bought, amongst other things, a number of prize-winning books.

Furthermore, we visited several institutions that had produced relevant publications for our collections: the University of Rwanda; the University of Kigali; Kigali Independent University (ULK); University of Lay Adventists of Kigali (UNILAK); the National Institute of Statistics; the Catholic NGO Caritas (which also exploits the bookshop); and the headquarters of one of the main daily newspapers, The New Times. As we had already discovered, papers were not sold on the streets. It was evident that COVID-19 had impacted the production of journals and newspapers. Print issues had been discouraged for health reasons, and while some were envisaging printing again, others will probably remain digital.

After one week, we returned with over 600 publications, several films on DVD, and a whole year’s worth of The New Times, all to be discovered in our library soon! Beginning next year, a (partly online) exhibition of the new Rwanda collection has been planned.

Elvire Eijkman (with contributions by Gerard van de Bruinhorst)