In the last weeks of 2021, the Netherlands Research Council launched a new type of research funding: the Embassy Science Fellowship. The call that caught my eye was for an Africanist scholar to work as embedded researcher in the Embassy of the Kingdom of the Netherlands in Jakarta, Indonesia. I applied out of curiosity and hunger for new challenges, and was fortunate to find myself with my family in Jakarta in the fall of 2022.

South-South cooperation

South-South cooperationThe Embassy’s call was inspired by conversations they had with Indonesian policy makers about Indonesia’s longstanding ambition and ideology centred on South-South cooperation and solidarity. The 1955 Bandung Asia-Africa Conference is illustrative of this, as is Indonesia’s role in the Non-Aligned Movement. The latter originated as an effort to counterbalance the rapid bi-polarisation of the world during the Cold War. The Netherlands, to maintain and foster strong connections with Indonesia today and in the future, invests a lot in the field of knowledge and knowledge relationships with Indonesian counterparts. In view of this, the Netherlands embassy asked me to contribute ‘to structurally strengthen Indonesian knowledge of Africa’ and relations with African countries’ research institutions. Working trilaterally with African countries in Indonesia aligns with the Dutch policy to work more often in multi-lateral settings with Indonesia, potentially enabling win-win-win situations.

Decolonising?

Yet, the assignment sits somewhat uncomfortable in these times of heated debates about the need to decolonise the Academy and of questioning the ethical grounds for Area Studies, including African Studies –particularly in the context of the Dutch former position as coloniser of the archipelago. This discomfort is perhaps even more intense when considering that the Dutch relationships in trade and knowledge with the African continent were developed at least partly as a reaction to the loss of its colonies in the East. The African Studies Centre Leiden, for instance, has its roots in this turbulent period of decolonisation and search for alternative trading routes. At the same time, like in the 1950s, more South-South and trilateral connections may support a more diverse global world order, which seems very much necessary as economic, health and climate challenges increasingly threaten our planet, peace and interconnected lives.

Africa in the Indonesian academy

Despite the long-standing ambition and ideology, and its more than 3000 universities, I found that in Indonesia ‘Africa’ is hardly visible in academia and the public at large. My search for Africa expertise in academia to connect with, sometimes felt like detective work. For instance, at world renowned universities with several thousand students in study programmes like International Relations, sometimes no or only one elective course included a focus on Africa. And often the programme coordinators and lecturers had not had the chance to develop their expertise by visiting the continent themselves. Similarly, the public image of Africa in Indonesia is strongly marked by stereotypes, or is absent altogether – and this feeds into diplomatic, academic and business relationships too. I was told, for instance, that delegations from African countries tend to be welcomed with much less attention and attire than delegates from countries from other parts of the world. Symbolically telling, perhaps, is that the flagpoles in front of the famous Asia-Afrika Conference museum look, more than anything else, like a fence (an Indonesian colleague rebutted jokingly that it is perhaps to shield this ‘hidden gem’ from the public eye. See top photo.)

Nation-building and national security

An important reason for this may lie in the fact that for many decades, during the ‘New Order’, universities were managed strongly top-down, while the government was focused mainly on nation building and national security – with research at the service of these aims. The ‘New Order’ refers to the period of rule of Indonesia’s second president, Suharto, from 1966-1998. In this period, Indonesian scholars were thus oriented mainly towards their own archipelago. Furthermore, dictates of global scientific research funding have long restricted (and still restrict) the agendas universities, institutes or individual scholars may pursue. Finally, contemporary economic ties with Africa have not yet been convincing enough to change these orientations. Indonesia, working hard to maintain a secured position as a middle-income country, seems more invested in advancing connections with countries and regions associated with economic growth and the knowledge economy than with world regions associated with less.

Turning point

Turning point

However, we may be on a turning point. Meeting colleagues at research institutes and universities, the enthusiastic reactions about connecting more with African scholars and universities cannot pass unnoticed. This may in part reflect how economic ties with African countries are increasingly recognised and sought. In addition, longstanding (and re/invented) connections along religious lines seem to play a role. The relatively new Universitas Islam Indonesia in Jakarta, for instance, is eager to build on those commonalities. Also, growing numbers of African students find their way to Indonesian higher education, some of them allegedly inspired by information shared by West African traders in the garment industry, many of whom work in Jakarta’s neighbourhood Tanah Abang.

Solidarity as motive

But more than that, Indonesia appears to see its (re)connecting in the world as part of finding and securing a new, more active place in the global world order. In this process, according to a political scientist I spoke to, Indonesia needs to strike a balance between ‘playing with the big guys’ and looking out for those in need of solidarity (to which they often count themselves or parts of the Indonesian archipelago, too). Telling indeed is that many of the growing numbers of African students in Indonesia arrived through a scholarship programme that seeks to provide educational opportunities for students from non-aligned countries; a programme that was developed decades ago. Thus showing how some of the ideals on South-South cooperation and solidarity continue to function as a motive in Indonesian policies and politics.

African perspectives?

African perspectives?

With the needed debates about decolonising the Academy in mind, Dutch participation in fostering South-South and trilateral knowledge collaboration requires reflexivity and modesty. At the same time, in light of the limited connections with Africa that developed in Indonesia over the past decades, one may wonder if the current pioneering developments will follow through without explicit attention and financial support from trilateral partners.

An even more interesting question is, however, how African counterparts experience these interests. To my knowledge, Indonesia may also not (yet) be so well known in the many African countries either. Are African publics and governments waiting for more companies and products like Indomie, one of the bigger Indonesian - instant noodle - companies that gained visible presence in, for instance, Nigeria and Tanzania? Are West-African countries waiting for Indonesian investments in the palm oil industry? And what does it mean to South African Muslims to rekindle historical ties with their Malay ancestors? Perhaps a next fellowship opportunity will allow to explore some of these ‘Indonesia in Africa’ questions, while continuing the conversation on how truly win-win-win inclusive academic collaboration may be achieved.

Would you like to stay updated on new blog posts in the ASCL Africanist Blog? Subscribe here! Would you like to comment? Please do! The ASCL reserves the right to edit, shorten or reject submitted comments.

Photos

Top photo: Museum Konferensi Asia Afrika, Bandung. Credit: BxHxTxCx (using album), CC BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons

Upper left photo: 'DR Congo': Reminding stones and signs of African delegates' presence during the Asia-Africa Conference on Bandung's streets. Credit: L.H. Berckmoes

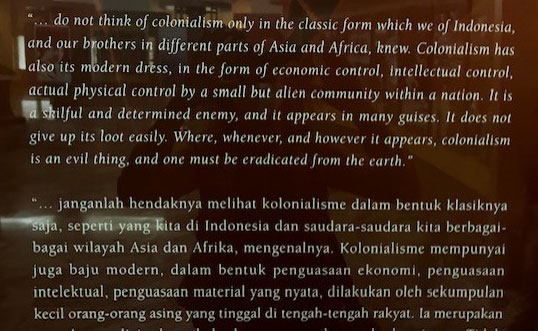

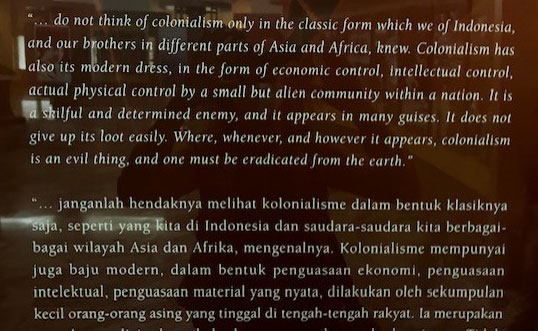

Photo right: Speech by former president Sukarno, denouncing all forms of colonialism, Asia-Africa Conference Museum, Bandung. Credit: L.H. Berckmoes

Middle photo left: African eatery by Malian migrant in Tanah Abang, Jakarta. Credit: L.H. Berckmoes

Lower photo left: African Trace Center in Tanah Abang, Jakarta

Lidewyde Berckmoes is an associate professor and senior researcher at the African Studies Centre Leiden.

Lidewyde Berckmoes is an associate professor and senior researcher at the African Studies Centre Leiden. South-South cooperation

South-South cooperation Yet, the assignment sits somewhat uncomfortable in these times of heated debates about the need to decolonise the Academy and of questioning the ethical grounds for Area Studies, including African Studies –particularly in the context of the Dutch former position as coloniser of the archipelago. This discomfort is perhaps even more intense when considering that the Dutch relationships in trade and knowledge with the African continent were developed at least partly as a reaction to the loss of its colonies in the East. The African Studies Centre Leiden, for instance, has its roots in this turbulent period of decolonisation and search for alternative trading routes. At the same time, like in the 1950s, more South-South and trilateral connections may support a more diverse global world order, which seems very much necessary as economic, health and climate challenges increasingly threaten our planet, peace and interconnected lives.

Yet, the assignment sits somewhat uncomfortable in these times of heated debates about the need to decolonise the Academy and of questioning the ethical grounds for Area Studies, including African Studies –particularly in the context of the Dutch former position as coloniser of the archipelago. This discomfort is perhaps even more intense when considering that the Dutch relationships in trade and knowledge with the African continent were developed at least partly as a reaction to the loss of its colonies in the East. The African Studies Centre Leiden, for instance, has its roots in this turbulent period of decolonisation and search for alternative trading routes. At the same time, like in the 1950s, more South-South and trilateral connections may support a more diverse global world order, which seems very much necessary as economic, health and climate challenges increasingly threaten our planet, peace and interconnected lives. Turning point

Turning point African perspectives?

African perspectives?

Add new comment