What’s all the fuss about micro-franchising by multinationals in Africa?

Harrison Esam Awuh is a postdoctoral researcher at the African Studies Centre Leiden. He is working on inclusive development and ecological sustainability. He has written this blog on behalf of the Collaborative Research Group Governance, entrepreneurship and inclusive development.

Harrison Esam Awuh is a postdoctoral researcher at the African Studies Centre Leiden. He is working on inclusive development and ecological sustainability. He has written this blog on behalf of the Collaborative Research Group Governance, entrepreneurship and inclusive development.

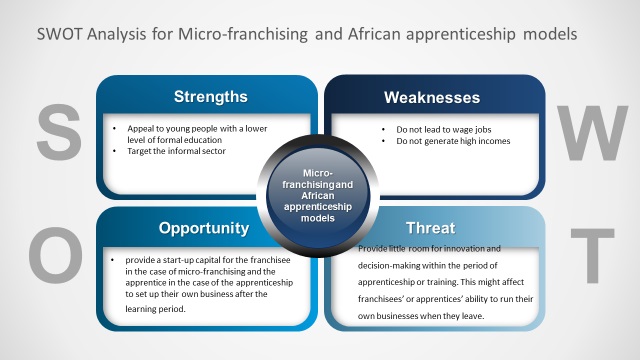

Growing up in Cameroon, I knew several ‘brothers and sisters’ who raised capital to start their own businesses. They did so by learning a trade or business by working for someone for a few years without pay, and being ‘settled’ at the end of the agreed period with a start-up capital for their own business. Considering this apprenticeship model has been a way out of poverty for many less educated people I grew up with, I am flabbergasted it has received little attention in academia. Instead, micro-franchising by big multinationals is increasingly heralded as the big thing in poverty eradication in Africa – for no good reason.

As a poverty eradication model for the informal sector, the micro-franchising business model by multinationals does not offer anything new or innovative in Sub-Saharan Africa. The model more or less replicates traditional African apprenticeship models. The novelty and innovativeness of the micro-franchising model lies in its use by large multinationals to access markets in developing countries and not poverty alleviation per se.

Innovative powdered milkshake

Innovative powdered milkshake

I watched the Hollywood movie ‘The Founder’, aired on the Dutch NPO channel on 15 March 2019 and it just confirmed to me how franchises and their smaller ‘cousins’ micro-franchises can stifle bottom-up innovation and decision making. ‘The Founder’ is a 2016 American biographical movie directed by John Lee Hancock and written by Robert Siegel. The film stars Michael Keaton as businessman Ray Kroc, and portrays the story of his creation of the McDonald's fast food chain franchise with the McDonald brothers (Richard James and Maurice James McDonald). In one scene the company is encountering higher than expected costs, particularly for refrigeration of large quantities of ice cream for milkshakes. A member of staff in one of the subsidiaries in Minnesota suggests an innovative powdered milkshake as a way to avoid these costs, but the McDonald brothers consider it incompatible with the company’s food quality standards and reject the innovation.

Traditional African apprenticeship model

By definition the micro-franchising model is a business approach in which large multinationals market consumer goods and services through micro-distribution agents (often ‘door-to-door’ and rural). An example is the Fan Milk distribution model in West Africa. Fan Milk is a Danish multinational enterprise which operates across most of West Africa. The micro-franchising model adopted by Fan Milk is increasingly associated with poverty alleviation through its purported ability to increase poor people’s incomes by providing them inputs needed for self-employment and entrepreneurial skills. However, the claim that it reduces poverty has never been thoroughly verified. In that sense, the micro-franchise model isn't different from the traditional African apprenticeship models. Most apprenticeships are provided by the private sector, sometimes for a fee, and lead to self-employment rather than to wage jobs.

The importance of social networks

There are two kinds of apprenticeships. In the first, the apprentice pays a fee for the apprenticeship, upfront. In the second, the apprentice provides labour and services instead of an upfront payment. In the latter, at the end of the agreed period of apprenticeship, the apprentice gets a start–up capital (in cash or equipment) to help in setting up own business (known as ‘settling’ in Cameroon and Nigeria). Entry into the latter category of traditional African apprenticeship is settled by social networks rather than the ability to pay a fee upfront. The employer or trainer needs to know the family or at least a family member of the potential apprentice personally, and vice versa, in order to instil trust between the two parties. The micro-franchise business model is comparable to these aforementioned approaches of the traditional African apprenticeship model. The models share a number of characteristics:

Lack of entrepreneurship training

However, as they do not lead to high-productivity jobs, traditional apprenticeships and micro-franchising in Sub-Saharan Africa fail to provide opportunities for their trainees or apprentices to generate high incomes. This could be largely due to a lack of entrepreneurship training. In fact, the traditional African apprenticeship model with no upfront payment offers a better opportunity for entry into the sector, whereas the micro-franchising model often requires franchisees to make an upfront payment in order to join the sector, for example with Fan Milk operations in West Africa.

No utopian image

Nevertheless, I resist the urge to present a utopian image of the African traditional apprenticeship business models, because this model is built on trust and trust can be broken. I know cases in which trainers or employers have exploited apprentices by refusing to provide the start-up capital at the end of the apprenticeship period, which was initially agreed upon. Also, changing market conditions could force the employer out of business before the ‘settling’ period.

Little room for input

Little room for input

The micro-franchising model and the African traditional apprenticeship models are more suitable for ‘necessity’ than for ‘opportunity’ franchisees or apprentices. A necessity franchisee just needs a job or a source of livelihood and the two models provide just that. An ‘opportunity’ franchisee or apprentice seeks to grow and exploit market opportunities. However, the structures of the micro-franchising and African apprenticeship models restrict decision-making and innovation. The learning process is strictly defined by the franchisor or the trainer with little room for input from the franchisee or apprentice. This rigidity inhibits the ability of the opportunity franchisee or apprentice to exploit emerging market opportunities. Likewise, in the franchising model as in the case of McDonald’s mentioned before, the franchisee is denied the role of opportunity franchisee by rigid structures of the company which only allow top-bottom flows of innovation and decision-making.

In order to be considered an innovative model in the domain of poverty alleviation and to surge beyond other existing models of poverty eradication in Africa, the micro-franchising model needs to provide opportunities for franchisees to develop real entrepreneurial qualities during the period of engagement – innovation and decision-making qualities. Or as Tony Falkenstein, a New Zealand entrepreneur, says:

‘To start a business does not necessarily make you an entrepreneur. Entrepreneurs “create needs”; business people “satisfy needs”’.

This post has been written for the ASCL Africanist Blog. Would you like to stay updated on new blog posts? Subscribe here! Would you like to comment? Please do! The ASCL reserves the right to edit, shorten or reject submitted comments.

Top and lower photo & SWOT analysis by Harrison Awuh.

Add new comment