Better securing Africa's food supply after COVID-19

This is a guest blog written by Bruno Parmentier, engineer, economist, author of Nourrir l’humanité and Faim zero (Editions La Découverte), Manger tous et bien (Editions du Seuil) and Agriculture, food and global warming (Internet diffusion), and host of the blog ‘Nourrir Manger’ and of the You Tube channel with the same name. He directed the Groupe Ecole Supérieure d’Agriculture d’Angers from 2002 until 2011.

This is a guest blog written by Bruno Parmentier, engineer, economist, author of Nourrir l’humanité and Faim zero (Editions La Découverte), Manger tous et bien (Editions du Seuil) and Agriculture, food and global warming (Internet diffusion), and host of the blog ‘Nourrir Manger’ and of the You Tube channel with the same name. He directed the Groupe Ecole Supérieure d’Agriculture d’Angers from 2002 until 2011.

Lire la version française ici ou en bas du blog.

It seems that, spring 2020, most of Africa has been little affected by the COVID-19 epidemic; no one will complain, because it would have done considerable damage given the weakness of Africa’s hospital structures. On the other hand, the economic damage caused by this global crisis could be major on the continent, and in particular to those linked to the food supply. In this region of the world, which imports a good part of its daily food, hunger is likely to kill many more people than the disease.

Hunger is only increasing in Africa

It is an understatement to say that African agriculture shows enormous signs of weakness; the continent has virtually no countries that are in a state of food security and independence, or that are substantial exporters of basic food products. While it is true that tropical products such as bananas, coffee, cocoa, peanut oil or cotton are produced there and sold abroad, cereals are massively imported into Africa. However, in the event of a major crisis, one can do without a small coffee, but not without "real" food, which simply provides the calories necessary for survival.

Asia and Latin America, which have also experienced many problems since the mid-twentieth century, have nevertheless managed to benefit from the agricultural revolution of the 1960s and now contain many big agricultural countries. Starting with the first of them, China, once emblematic of the world hunger, has now reached the top of world production for most agricultural products: rice, of course, but also wheat, fruits, vegetables, eggs, meat, cotton, etc. In terms of corn, it is "only" the 2nd largest producer in the world, and 5th in soybeans. It is only for dairy products that China stands still, given the low appetite of its population for those foods. India, Vietnam, Indonesia, Thailand and many others have also become major agricultural countries. One could cite Latin America, where Mexico has certainly fallen slightly behind, and where Venezuela suffers from hunger once more, but it is needless to name Brazil and Argentina, or Uruguay, which not only manage to feed themselves, but also contribute actively to feed other parts of the world.

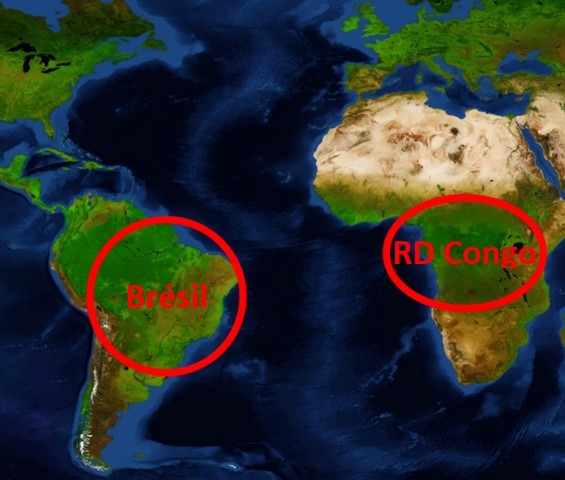

Why can we not cite a single African country in this list? Why, for instance, has the Democratic Republic of the Congo, which from a geographical point of view is to Africa what Brazil is to America, not yet become a major exporter of agricultural products but rather one of the homelands of hunger? Will it be necessary to wait for the closure of the last diamond and copper mines so that the country ceases to interest the great greedy world powers (which in fact provoke an uninterrupted succession of wars, which are very unfavourable for agriculture), so that it finally reaches its true vocation: actively contributing to feeding humanity?

Why can we not cite a single African country in this list? Why, for instance, has the Democratic Republic of the Congo, which from a geographical point of view is to Africa what Brazil is to America, not yet become a major exporter of agricultural products but rather one of the homelands of hunger? Will it be necessary to wait for the closure of the last diamond and copper mines so that the country ceases to interest the great greedy world powers (which in fact provoke an uninterrupted succession of wars, which are very unfavourable for agriculture), so that it finally reaches its true vocation: actively contributing to feeding humanity?

Can we be satisfied with the observation that hunger has very sharply declined in most regions of the world, but that the overall figure of around 800 million people who suffer from it remains very stable on a global scale? It is the number we already observed in 1900, but also in 1950 and in 2000, although the world population increased by almost 6 billion people in the period. World agriculture has therefore made absolutely considerable progress in being able to feed 6 billion more people from the same fields... except in Africa. In fact, everything happens as if hunger were now concentrating in two, and only two, regions of the world: the Indo-Pakistan peninsula, where it remains stable, and subtropical Africa, where it continues to increase (more obviously some countries still at war in the Middle East). However, those are likely the regions of the world that will suffer the most from the effects of global warming, which will in particular make the action of producing food much more difficult.

Hunger has become a 100% human construction

Note that in the meantime, hunger has changed status: it was a natural and inevitable phenomenon, a kind of fatality or product of ignorance, from the time when we were neither good at agriculture nor at international transport. Any climate problem, illness or epidemic, any locust cloud, any hurricane or earthquake, etc. was enough to cause famine. But we are no longer at that stage: hunger no longer has a fatal character, it has become a 100% human construction, since we have the technical means to resolve it; it is henceforth the pure product of greed, carelessness and indifference of men, therefore an eminently political problem, and its elimination is essentially a matter of political action.

It’s hard to eat alone

Almost all of the countries that have become major independent agricultural powers have had a large area and a substantial population. As agricultural production is very dependent on the climate, it is important to bring together regions which have relatively different climates, so that a climatic incident in a well-defined area does not compromise the supply as a whole within the nation.

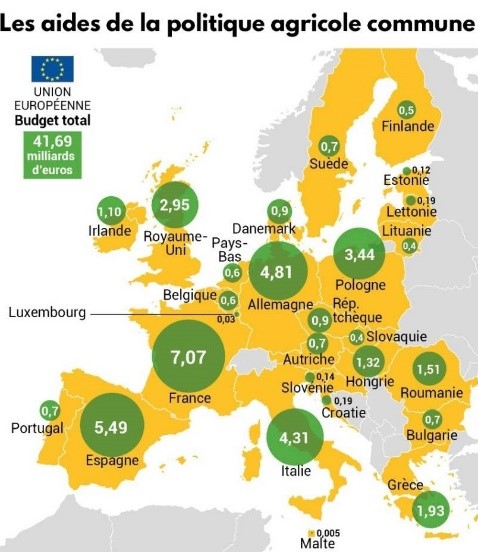

This is of course the case in China, India, the United States, Canada or Brazil. And in the case of Europe as well, which is however essentially made up of small countries, it was the grouping of 6 countries at the start, which have now become 28, which made it possible to achieve the objective. And since it is quite unlikely that the same climatic incident would seriously affect Greece and Finland at the same time, or Poland and Portugal, it is easier to stabilize production year after year; in addition, the range of products that can be grown is much wider by grouping very different soil and climate zones. And 440 million citizens can come together more effectively to invest heavily in the modernisation of their agriculture and the protection of their borders. It worked: European agricultural production has tripled since the 1960s.

This is of course the case in China, India, the United States, Canada or Brazil. And in the case of Europe as well, which is however essentially made up of small countries, it was the grouping of 6 countries at the start, which have now become 28, which made it possible to achieve the objective. And since it is quite unlikely that the same climatic incident would seriously affect Greece and Finland at the same time, or Poland and Portugal, it is easier to stabilize production year after year; in addition, the range of products that can be grown is much wider by grouping very different soil and climate zones. And 440 million citizens can come together more effectively to invest heavily in the modernisation of their agriculture and the protection of their borders. It worked: European agricultural production has tripled since the 1960s.

This absolutely exemplary case of the development of the common European agricultural policy could perhaps also inspire some Africans. It has been a considerable advance in a continent where war has been waged for millennia; personally, I note that my great-grandfather fought against Germany, as did my grandfather, and that my father followed in their footsteps; however, in the Sixties, de Gaulle and Adenauer had the immense wisdom to break this fatality. So I had the privilege of not having had to wage war against Germany, and one of my sons even ended up marrying a German woman.

As a result, during this major COVID-19 crisis, all confined Europeans were able to eat their fill, including in the numerous countries on the continent where farmers are radically incapable of producing enough food for their population.

So, to modernize agriculture in a really significant way, it seems useful and effective to group together large areas where it is possible to invest heavily in order to feed the local population, while at the same time, protecting the common borders from low-priced imports which are ruining agriculture during the process of modernization.

What agricultural groupings should be made in Africa?

What agricultural groupings should be made in Africa?

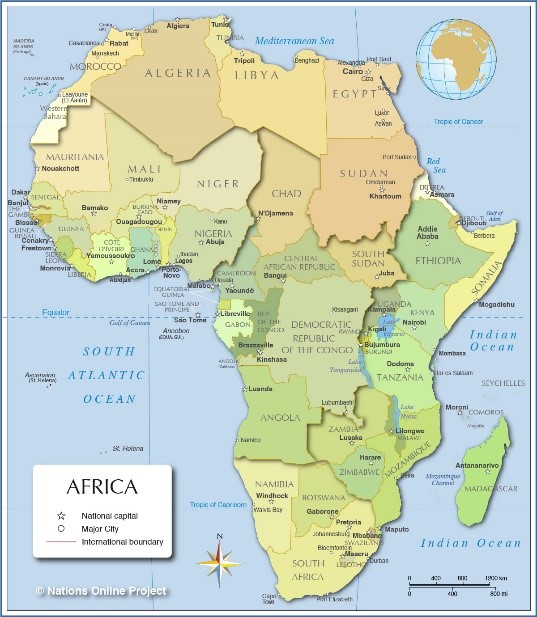

It is likely that, from a purely theoretical point of view, there would be room for 4 to 6 groupings which would make sense to establish common agricultural policies in Africa. Together they would unite both dry and wet countries, like, in the west, an entity going from Senegal to Niger and Nigeria, another going from Gabon to Zambia, or even in the east from Sudan to Kenya, or from Tanzania to South Africa. The chances of such groupings gaining a certain level of food autonomy would then be real. Does this seem totally unrealistic and utopian? But, in 1939, who thought that a common European agricultural policy was possible, and more, a democratic one?

Difficulties of all kinds to overcome the bitterness, the legacies of history, the differences in culture, languages, ethnicities, etc. are certainly absolutely immense, and the support of the great external powers which covet the natural wealth of these regions absolutely not guaranteed: they obviously prefer to continue dividing to keep their grip, whatever the cost (in African lives!).

But we must also realise that the population of these regions will double by 2050, and that, given the current agricultural weaknesses, it would really be necessary to triple agricultural production at the same time to hope to achieve food self-sufficiency. Precisely what Europe managed to do between the 60s and the 90s, by the way.

In addition, they will have to face the dramatic consequences of global warming. And, in this necessary and vital agricultural revolution, there should be no mistake about the century in which we live. Let us therefore forget the idea of finally implementing, with 50 years of delay, the agricultural revolution of the 60s, that of “all chemistry-all petroleum”, based on tractors, plowing, fertilizers, pesticides, etc. – when these are showing their limits in Northern countries today (it has already been over 20 years since yields have increased in Europe and North America).

It is perfectly possible to triple the agricultural production of subtropical Africa

It is now time for the agroecological revolution, which relies on the forces of nature rather than on fighting against them. Two major reasons for this: first, we are beginning to get to understand the infinitely small elements that make up the soil, such as bacteria, fungi and other microscopic organisms; we will finally be able to use this acquired knowledge to our advantage. Second, in tropical countries with low productivity today, precisely, the forces of nature are enormous, and suddenly we can reasonably hope to capitalise on the centuries-old traditional experience of local farmers to make huge gains in productivity by clearly more “natural” methods, which consume less capital, and which also provide more employment. It is perfectly possible to triple the agricultural production of subtropical Africa, by agro-ecological methods, by finally finding the favourable socio-political conditions to do so; but here again, groupings into larger and diversified entities seem to constitute an absolutely essential condition for having real chances of success.

Is the agricultural future of the Maghreb to be found looking North or South?

The situation is quite different in North Africa. On the one hand, these countries will face a situation of very great drought, which will worsen with global warming. On the other hand, the Sahara barrier, coupled with great cultural differences, still makes it impractical to envisage a common agricultural policy which would bring together countries from Algeria to Côte d'Ivoire. And finally, an alliance, perhaps easier culturally, of the countries going from Egypt to Morocco or Mauritania, does not allow diversification of the climates and therefore does not really secure the food supply. A large country like Egypt, which already has a hundred million inhabitants, will never manage to feed itself when it only has 4% of cultivable land (because irrigable), the rest being made up of absolute deserts, unfit for agriculture. This country is already, year after year, the first importer of wheat in the world and it is illusory to think that the Moroccan or Algerian peasants will be able to feed it.

The poverty and the growing insecurity in the countries of the Sahel and of tropical Africa are generating migration, which will only increase towards the European countries, which are considered, despite their obvious racism and selfishness, less hopeless than the homelands. We are only at the very beginning of this process. Isn't it time to look at history differently, and especially geography? If we consider that the Mediterranean is an inland sea, and that its riparian countries still have a common future, we can observe that, in the decades to come, the regions of the North of the Mediterranean have every chance of remaining in surplus in food, particularly in cereals, while the southern regions of the Mediterranean are going to have an increasingly vital need to import it.

The poverty and the growing insecurity in the countries of the Sahel and of tropical Africa are generating migration, which will only increase towards the European countries, which are considered, despite their obvious racism and selfishness, less hopeless than the homelands. We are only at the very beginning of this process. Isn't it time to look at history differently, and especially geography? If we consider that the Mediterranean is an inland sea, and that its riparian countries still have a common future, we can observe that, in the decades to come, the regions of the North of the Mediterranean have every chance of remaining in surplus in food, particularly in cereals, while the southern regions of the Mediterranean are going to have an increasingly vital need to import it.

Is an enlargement of the European common agricultural policy really so far-fetched?

But also, if one observes Morocco, one realises that, from its point of view, there is a chance to be able to produce fruit and vegetables earlier and cheaper to supply the immense common market of 440 million Europeans. Besides, as of today, Morocco's food trade balance is roughly balanced: they buy about as much grain as they sell fruits and vegetables, and the Strait of Gibraltar is very easy and quick to pass for its trucks. Algeria, which has largely relied on the ease of exploiting oil and gas without investing in its agriculture, finds itself, with a food trade balance in deficit of around 9 billion euros annually, as much as Egypt. It has only started in recent years to make real agricultural investments, relying mainly on the Chinese, but, in matter of food, China is far away. Since decolonisation, France has tripled its agricultural production, and Algeria has tripled its population, but it still has - let's look at it positively - kept real reserves of agricultural productivity.

Is an enlargement of the European common agricultural policy towards a Mediterranean common agricultural policy really so far-fetched? Many Europeans will not fail to wonder with what the Maghrebis will be able to pay for the food which they will send to them; we can point out that currently Egypt and Algeria do actually pay for the wheat they buy from the French and Ukrainians, and Morocco too, the latter with euros largely earned by selling back to them tomatoes, zucchini, melons and red fruits.

Is an enlargement of the European common agricultural policy towards a Mediterranean common agricultural policy really so far-fetched? Many Europeans will not fail to wonder with what the Maghrebis will be able to pay for the food which they will send to them; we can point out that currently Egypt and Algeria do actually pay for the wheat they buy from the French and Ukrainians, and Morocco too, the latter with euros largely earned by selling back to them tomatoes, zucchini, melons and red fruits.

But we can also make these sceptic Europeans realise that, if hunger continues to increase in Africa, from North to South, they could end up paying for it very dearly. It’s not such a bad investment for the future to get your neighbours to eat.

As to the Maghrebis, who remain rightly traumatised by the violence of colonialism and neocolonialism, and especially do not want to repeat the experience, we can make them see that a common agricultural policy can be democratic, if it is the will of all the parties. And that it is not a recolonisation of Algeria by France, but a free alliance between blocks of countries, in order to advance their common interests.

It is obviously not a question of purely and simply enlarging the European Union in the Maghreb, as some have thought of doing before with Turkey, but rather of making win-win agreements, probably including both food and energy. After all, it was the agreement on coal and steel and then agricultural policy that changed the idea of a common future for Europeans who had spent centuries waging war.

Can Africa afford a real agricultural policy?

The establishment of a “real” agricultural policy requires very strong political will for many years, accompanied by relatively large financial means. Is it unrealistic to think that Africa could get there? It is true that Europe in the 1950s and 1960s was much richer than today's Africa; it was industrialised and had long established relatively efficient political and administrative systems. But it came out of a merciless war that had largely destroyed its industrial potential. The development of its agriculture owes a lot to the famous Marshall Plan: for fear of an extension of communism in Western Europe, the Americans did not hesitate to invest massively in it to reduce poverty and restart the economic machine. Tens of thousands of tractors, combine harvesters, plus fertilisers, pesticides and selected seeds crossed the Atlantic (creating new markets for US companies).

In the same way, one can observe that an identical fear of extension of communism from China to India was a powerful motivation for the invention of the "Green Revolution" and its extension in Asia, which was worth the Nobel Peace Prize to Norman Borlaug; it has been estimated that it has saved hundreds of millions of lives. And incidentally, in both cases, "generous America" profited there, and took the opportunity to develop itself considerably.

So fighting hunger is expensive? But what about malnutrition, hunger and famine and all their consequences, for the populations concerned of course, but also for world peace? Can we really not mobilise real international funding to eradicate this hunger pandemic?

Note, however, that with agroecological farming, the cost of the "entry ticket" has decreased considerably. This new agriculture is much less mechanised and much less capitalised than the previous one. It first calls on grey matter and labour. It is no longer a question of sending hundreds of freighters loaded with sophisticated machines.

And this funding must come primarily from the countries concerned themselves. Let us observe the now famous, so-called "Zero Hunger" policy implemented in Brazil in the early 2000s, and which has now become a major objective of the United Nations. It consisted in reinventing family allowances with subsidies of $ 40 per child per month, directed only at food purchases, coupled with a strengthening of family farming, public purchases of food products and a training system, risk management and price regulation. Its results have been absolutely spectacular in a very short time: this programme has enabled 20 million Brazilians to get out of poverty (they went from 28% to 10% of the population), reduced child malnutrition by 61%, child mortality by 45% and rural poverty by 15%, by promoting local agriculture and the consumption of local products. All of these actions have been funded by the country itself. In the name of what could this not be applicable to other continents?

Would you like to stay updated on new blog posts in the ASCL Africanist Blog? Subscribe here! Would you like to comment? Please do! The ASCL reserves the right to edit, shorten or reject submitted comments. Read the other blog posts dealing with COVID-19.

Photo credits

Top photo: Fadiouth women preparing millet to make couscous flour, Senegal. Photo by Apostrophekola-real via Wikimedia Commons / CC BY-SA.

Other photos derived from presentations by Bruno Parmentier.

Read an interview with Bruno Parmentier in Dutch newspaper NRC Handelsblad (22 May 2020).

Add new comment